“I see myself as a huge fiery comet, a shooting star. Everyone stops, points up and gasps ‘Oh, look at that!’ Then whoosh, and I’m gone…and they’ll never see anything like it ever again…and they won’t be able to forget me—ever.”

—Jim Morrison

***

What we do not get from Morrison—as a person with a full range of human complexities—is a single perspective or fixed point on how to interpret him or his era. He is part of a larger puzzle for understanding the Sixties and early Seventies. What I argue, along with other historians, is that history is the craft of presenting information based on viewpoints, analysis, documentation, and other points of reference, but not what actually happened. Even if you were beside Jim as he lived his life, it would not be history but rather your interpretation of that time frame from your own perspective. Historians create the framework.

This is important in examining and piecing together a contentious era like the Sixties. We are attempting to shine light into the dark night that brings together the lived experiences and lifetimes of people who valued the time for different reasons. For example, I contend that it is impossible to comprehend the Sixties without layering in Vietnam, whether economic, political, or cultural. However, I’ve interviewed people who have never mentioned the war or its consequences on their lives. It is not as if these individuals lived in an alternate reality; it’s just that they found a way to circumvent the topic in a way that makes sense to them in their recollections.

Even when examining the parts of the Sixties that seemed to flow logically into the next, for example, as if the self-help and meditation of the 1970s had to be the outcome of the free-love and activist 1960s, we understand this equation is never the straight line it might appear to be on paper, film, or video. In fact, when it does seem like a direct path, it’s most likely that someone has created that narrative.

For literary critic Morris Dickstein, who grew up in the 1960s, a multitude of influences melded to create the era’s foundation: “The cold war, the bomb, the draft, and the Vietnam War gave young people a premature look at the dark side of our national life, at the same time that it galvanized many older people already jaded in their pessimism.” The role the Doors played in exposing the dark side and bringing it to the mainstream is significant.

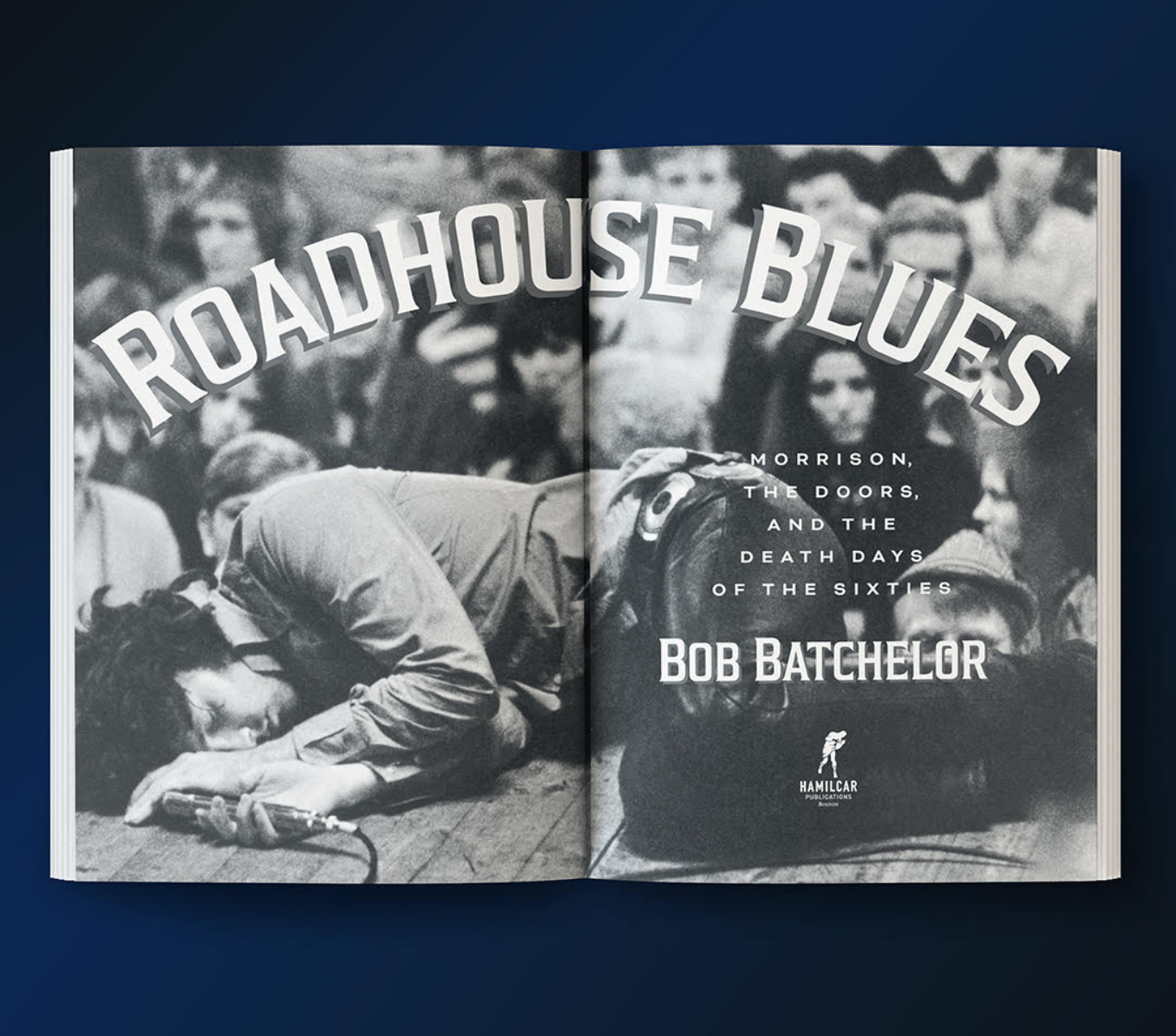

The depth of Morrison’s life called for writing this book. Few cultural icons have had a more lasting impact. But, as I have shown, the importance of the Doors includes the group too. It wasn’t strictly the Jim Morrison show, although his myth is of course a big factor in the band’s enduring fame.

This book is a reassessment of a significant era in American history and an example of how we might gain from that exercise. According to David Strutton and David G. Taylor: “The examination of history allows one to acquire experience by proxy; that is, learning from the harsh or redemptive experiences of others…Mythology is less reliable than history as narrative of actual experience; yet it may hold more power than history.”

By revisiting Morrison, the Doors, and the death days of the Sixties, we give the era meaning as it existed in its day and at the same time create a tool to use to navigate our lives and the future. For example, Vietnam has become synonymous with America’s intervention in overseas wars, particularly against enemies that appear doomed on paper. The wars in the Middle East over the last several decades have been examined via the Vietnam lens, but the comparison sadly did not lead to a different outcome. In this case—and concerning future warfare—we might ask ourselves the reasonable question: Where were the protesters who played such a pivotal role in illuminating what was happening in Southeast Asia in the Sixties and Seventies? For that matter, why were the journalists in the Middle East “embedded” rather than emboldened like their media forbearers? Perhaps the most significant difference was the draft, but the real emphasis is that reevaluating the decades gives a measure of what is happening today—and offers a potential lens for anticipating the future.

***

We all need tools to examine society’s larger questions, but Morrison’s life can also help us understand each other on a more intimate level. How did Jim view himself in the world?

One of the most striking aspects of Jim’s life versus the legend that grew after he died is the gap between what people thought of the public person versus the more private individual. After his death, the mythmaking and apocryphal aspects of his life seemed to eclipse who he really was.

For example, journalist Michael Cuscuna said, “The antithesis of his extroverted stage personality, the private Morrison speaks slowly and quietly with little evident emotion, reflectively collecting his thoughts before he talks. No ego, no pretensions.” For writer Dylan Jones, Jim stood as “the first rock’n’roll method actor” and “an intellectual in a snakeskin suit.” Ultimately, hinting at the singer’s true nature, he saw “a man who, when he revealed himself, was often to be found simply acting out his own fantasies.”

Jim embraced this notion of self-creation and wore different masks publicly and privately. In 1968, Morrison admitted that his image as the Lizard King was “all done tongue-in-cheek.” He explained, “It’s not to be taken seriously. It’s like if you play the villain in a Western that doesn’t mean that’s you.” But the singer cautioned, “I don’t think people realize that.” Were these really different masks for Morrison, or did the true Jim get lost (or stuck) in the alcoholic stupor?

Before the band hit the big time, there were some musicians and hippies in Los Angeles who saw Jim as little more than a poseur, as someone who wanted to become part of the scene and yearned for attention and approval. They saw him not as a poet but as just another lost angel longing for fame and fortune in the City of Lights.

A foundational aspect of human life is the need to create meaning. People engage in this activity from birth, investigating and examining the world in relation to other people and things around them. This type of exploration is called semiotics, which in plain terms means asking what something means in relation to ourselves and others. From this vantage point, Morrison’s public persona was cast in symbolic terms, like how a celebrity/star acted and what they could get away with versus noncelebrities. When he yelled out, “I am the Lizard King…I can do anything!” it seemed he believed it—at least the version of Jim who had assumed that symbolic role.

People use symbols, then, to adapt to a complex world that contains an enormous amount of abstraction. Krieger pinned Morrison’s worldview on his antiauthority nature. “You couldn’t tell Jim Morrison what to do. And if you tried he would make you regret it,” the guitarist recalled. “He was forever rebelling against his navy officer father. Anyone who attempted to step into a role of authority over him became the target of his unresolved rage.” What he learned to lash out at was not his powerful father but those in authority who attempted to control him.

Psychotherapist Jeannine Vegh saw the lasting effects of growing up in a military family. “Jim suffered from a crisis in his mind. His words seem destined for a prophet, but, instead, he succumbed to drink and drugs. I assumed that he had been exposed to some form of family trauma.” She believes it may have been that his parents preferred “dressing down” to other forms of punishment. “When a child is berated and humiliated in front of others, it takes a toll on them spiritually, physically, and mentally.” The turmoil from this kind of upbringing is a clear factor in Jim basically disowning his parents even before he became famous. When his father told him that joining a band was stupid, he never forgave him and never spoke to him again.

Morrison, by studying film, literature, and sociology, understood more deeply and theoretically what his contemporaries like Jagger, McCartney, Lennon, and Joplin knew—fame served as one of many disguises he had to wear as a rock star. For Jim, there was the hyperindividual aspect of fronting a band and presenting himself to an audience and then there was the other piece of it, the communal vibe from the collective experience. That high from being on stage—the rush of emotion, the intensity, the energy—was likely another form of addiction for him.

When in his rock star guise, Jim could also turn into the hideous performer, especially when drunk. If Morrison didn’t feel or perceive what he wanted from the audience, he turned against them, essentially doing what he did in one-on-one relationships: goad and aggressively provoke a reaction—any reaction. “I don’t feel I’ve really done a complete thing unless we’ve gotten everyone in the theater on kind of a common ground,” he said. “Sometimes I just stop the song and just let out a long silence, let out all the latent hostilities and uneasiness and tensions before we get everyone together.”

Yet whether the show went well frequently depended on the other principal ingredient—alcohol. The booze distorted his perceptions, which the singer believed helped him reach new horizons, but the mixed-up sensitivities of an alcohol-addled mind washed out of him in ways that neither he nor the band completely understood. Misperception led to the attempted riot and arrest in New Haven and the beginning-of-the-end Miami incident.

Morrison realized and manipulated the power he possessed as rock star and purposely baited the crowd in ways that were new to them. A person going to a concert has expectations and understands (roughly) how they should act as a part of the community. The Doors, however, constantly messed with that pact because it titillated Jim’s worldview and allowed him to see both his true self and his growing authority after a lifetime of poking at the figures and institutions of power in his life. Morrison told a reporter: “I like to see how long they can stand it, and just when they’re about to crack, I let ’em go.”

Once questioned about what might happen to him if the crowd turned, even threatening his own safety, Jim responded in typical narcissistic fashion, claiming, “I always know exactly when to do it.” Rather than fear them or what they might do to him, he craved control over the masses. “That excites people…They get frightened, and fear is very exciting. People like to get scared.” Intensifying his controversial comments, he used sex as an analogy: “It’s exactly like the moment before you have an orgasm. Everybody wants that. It’s a peaking experience.” The domination over the crowd and its collective retort fascinated and mesmerized Morrison. He could directly influence their experience or lead the band into a frenzy—with Ray and Robby urging the emotional response while John pounded out a driving beat.

Examining Bob Dylan’s career, you can see similar uses of the mask metaphor as a way to make sense of complexity and abstraction. In the early 1970s, Dylan faced a period of agitation as he coped with the decline of his marriage to his wife Sara. Looking back on the period, he spoke about the many sides of himself that existed and kind of threw him off-kilter. Dylan explained: “I was constantly being intermingled with myself, and all the different selves that were in there, until this one left, then that one left, and I finally got down to the one that I was familiar with.”

To cope with fame, Dylan constantly created new personas and masks. He could alternatively exist as a singer, writer, musician, revolutionary, poet, degenerate, or any of the other labels that might be thrust at him. Dylan even spoke about himself in the third person to underscore the difference between him and the character named “Bob Dylan.”

Obviously, while there is ultimately a person there—waking each day, eating, working, daydreaming, bathing—there is another aspect of Dylan that defies simple definition. Dylan, a member of an elite category of iconic figures, exists outside his physical form and represents numerous meanings that give people a tool to interpret the world around them. As a result, the artist isn’t only a member of society but a set of interpretations and symbols that help others generate meaning. As fans and onlookers, people are familiar with this tradeoff. They accept it with each side gaining something in the exchange. A regular human being could never have handled the pressure of being called the spokesperson of a generation. Instead, Dylan used different personas to compartmentalize and make sense of it—until he snapped under the weight of drugs and booze and used a motorcycle accident in 1966 as an excuse to drop out. Some would call Dylan’s breakdown a natural result of a burden too heavy to carry.

The difference between Dylan and Morrison is that the latter died before he had to confront these many roles. In death, these roles are assigned to Morrison by fans, critics, historians, and observers. Both icons might ask—if possible—that we define them by the songs they created or the lyrics they wrote, but the larger culture wants so much more. There is an image that must be created, managed, and maintained. Once someone becomes famous or iconic, they hold two identities—symbol and person.

Yet according to Evan Palazzo of the Hot Sardines, the power of the music is the real testament to the Doors. “Imagine if you were a concert buff in 1968, 1969, 1970, the bands you could see live, it was unparalleled. We don’t have anything like that today,” he explains. “But if they were a new band, the Doors would blow everyone out of the water—it would be seismic.”