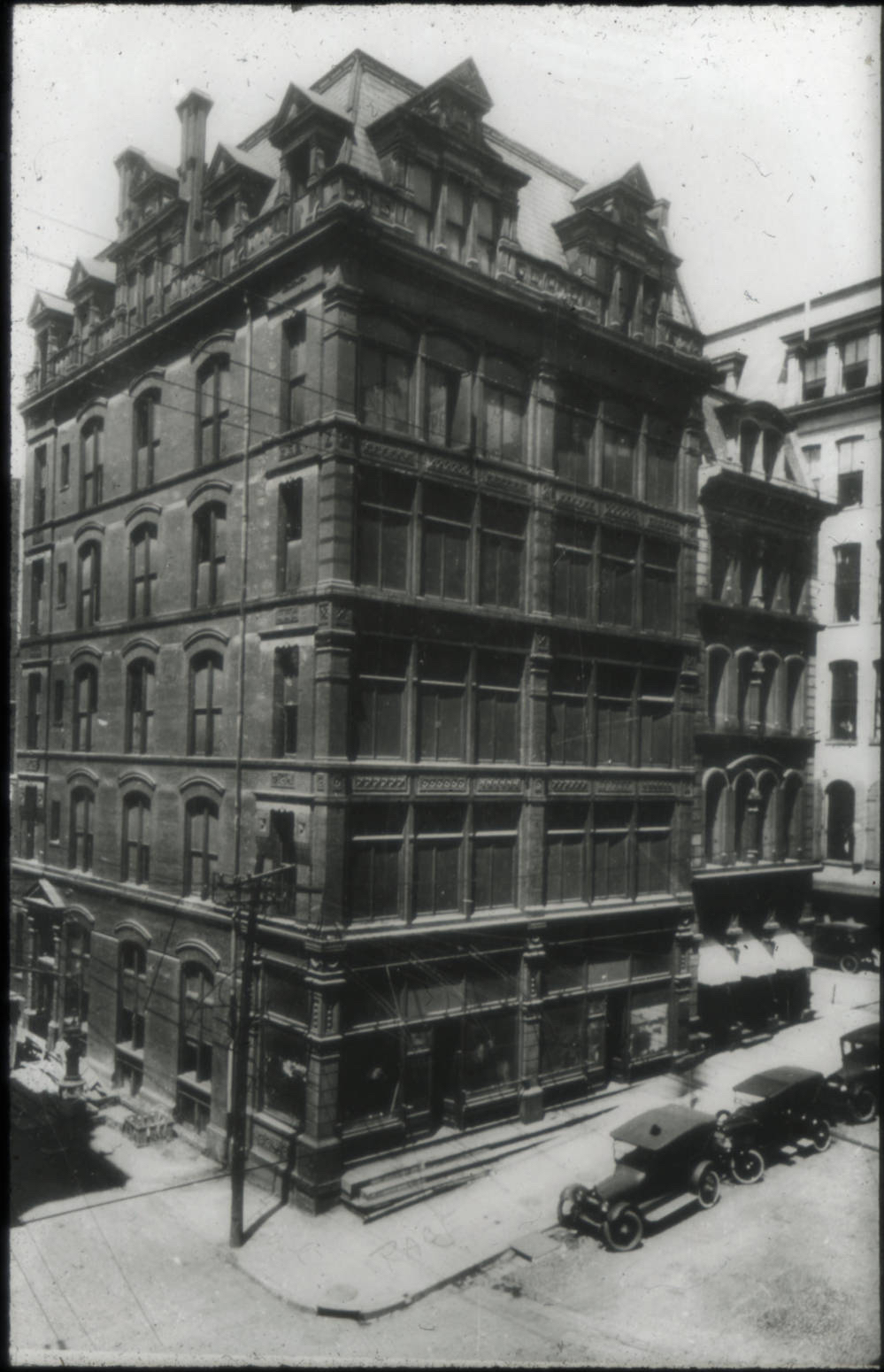

Can we learn from Prohibition in thinking about issues regarding the legalization of marijuana?

My favorite history books provide deep insight the issues of the past and act as a kind of guide for addressing contemporary concerns. I had this idea in mind when writing The Bourbon King — how do we think about marijuana and other lifestyle choices regulated and legislated by the government?

We are still learning the lessons of Prohibition a century later. The most destructive aspect of the dry era was that it took a significant human toll on America.

Many lives were wasted, from people poisoned by tainted alcohol to those killed in enforcing the Volstead Act or attempting to circumvent the law. We have seen similar scenarios play out over the last several decades with marijuana legislation and enforcement.

During Prohibition and with weed over the last several decades, a significant air of lawlessness became commonplace. The nation still deals with these issues now. For instance, people travel between states that have legalized recreational and medical marijuana and those that still criminalize it.

Texas Senator Morris Sheppard, the “father of Prohibition”

We are still learning the lessons of Prohibition a century later…Many lives were wasted…a major human toll on America…We have seen similar scenarios play out over the last several decades with marijuana legislation and enforcement.