A Fact-Filled, Frequently Asked Question by Stan Fans Everywhere!

Pearl Harbor brought the war to America. Winning hinged on creating an interlocked infrastructure to support the troops. Businesses of all sizes rallied to the cause. Democracy hung in the balance!

Although still a teenager, Stan Lee enlisted on November 9, 1942, just as the US faced its first skirmish on the coast of North Africa. He took the Army General Classification Test and scored high, qualifying for the Signal Corps.

The war was good for comic books. In 1943 more than 140 were on newsstands, reportedly “read by over fifty million people each month.” In 1944, Fawcett’s Captain Marvel Adventures sold 14 million copies (up 21 percent). Superhero titles drove sales, but publishers also expanded into humor, funny animals, and teen romance. Captain America remained Timely’s most popular series.

“How would you like my job?” Lee asked his friend Vince Fago.

Veteran animator Fago had worked on Superman and Popeye for Fleischer Studios. Battling with Disney, Max Fleischer’s shop differed by focusing on human characters, such as Betty Boop and Koko the Clown, rather than talking mice, ducks, and other anthropomorphic figures. Martin Goodman paid Fago $250 a week.

The fighting overseas was heavy stuff; readers yearned for lighter comedic fare. Fago specialized in funny animals, so Timely used Disney as a model, essentially transforming into Disney-lite. They published amusing animal tales, such as Comedy Comics and Joker Comics. Lee had concocted some of these characters, like Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal (co-created with artist Al Jaffee, the future Mad magazine illustrator). Fago estimated that each comic had a print run of about 500,000. “Sometimes we’d put out five books a week or more,” Fago remembered. “You’d see the numbers come back and could tell that Goodman was a millionaire.”

Goodman also wanted to gain female readers. Miss America, a teenage heiress who gained superhuman strength and the ability to fly after being struck by lightning, first appeared in Marvel Mystery Comics #49 (November 1943), with Human Torch and Toro on the cover thwarting a Japanese battleship. In January 1944, Miss America became a title character. However, when sales dropped, the next issue was delayed until November, publishing as Miss America Magazine #2. A real-life model portrayed the character in her superhero outfit. For the relaunch, Fago and his team gradually eliminated superhero material in favor of topics deemed more appropriate for teen girls.

***

Lee went through basic training at Fort Monmouth, an enormous base in New Jersey that housed the Signal Corps. It also served as a research center – radar was developed there and the handheld walkie-talkie. In subsequent years, they would learn to bounce radio waves off the moon.

Stan Lee with his beat-up jalopy

Stan learned how to string and repair communications lines – a path to combat duty (like his former boss Jack Kirby). Army strategists knew wars were often won by infrastructure – the Signal Corps kept communications flowing, but they could barely keep up with demand. Other training centers opened at Camp Crowder, Missouri, and Camp Kohler, near Sacramento. By mid-1943, the Corps’ consisted of 27,000 officers and 287,000 enlisted men, backed by another 50,000 civilians.

Pearl Harbor heightened concern that German subs or planes might mount a surprise attack during the cold New Jersey winter. Lee patrolled the base perimeter, claiming the frigid wind whipping off the Atlantic nearly froze him to death.

The beachfront burden ended when Lee’s superior officers discovered his work in publishing. They placed him in a special outfit producing instructional films and other wartime materials. Lee wrote fast and in a breezy style that recruits and trainees could comprehend.

The Army liked these traits too. At the Training Film Division, based in Astoria, Queens, he joined eight other artists, filmmakers, and writers to create public relations pieces, propaganda materials, and information-sharing documents. Education was critical for the war effort. Imagine, millions of young Americans were enlisting and they collectively had about an eighth grade education. They needed to learn how to fire machine guns, run offices, and build bridges, barracks, and other essentials necessary to win the war. They needed training materials that they could understand and put to immediate use.

The Army purchased a large building flanked by rows of tall, narrow windows at 35th Avenue and 35th Street. Colonel Melvin E. Gillette commanded the efforts. Inside the Army built the largest soundstage on the East Coast, enabling filmmakers to create a variety of military settings and scenes. The old movie studio (built in 1919) soon rivaled the major Hollywood production companies.

Prop department at the Long Island facility

“I wrote training films, I wrote film scripts, I did posters, I wrote instructional manuals,” Lee said. “I was one of the great teachers of our time!” The Signal Corps group included many famous or soon-to-be-famous individuals, including three-time Academy-award winning director Frank Capra, New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams, and children’s book writer and illustrator Theodor Geisel, who the world already knew as “Dr. Seuss.” The stories that must have floated around during staff meetings!

Lee took up a desk in the scriptwriter bullpen, to the right of eminent author William Saroyan – at least when the pacifist author visited the office. Saroyan, who had won a Pulitzer Prize (but rejected it) for his play The Time of Your Life (1939), usually worked from a Manhattan hotel. Lee and the others, including screenwriter Ivan Goff and producer Hunt Stromberg Jr., earned the official Army military occupation specialty designation: “playwright.”

As home front efforts intensified, Lee traveled to other bases, essentially crisscrossing the Southeast and Midwest. Each base had a critical need for easy-to-understand manuals, films, and public relations documents. Stan wrote about using combat cameras, caring for weapons, and other topics he knew little about. In these situations, he utilized a familiar motto – simplify the information. “I often wrote entire training manuals in the form of comic books. It was an excellent way of educating and communicating.”

One post took Lee to Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indiana, just northeast of Indianapolis – a jarring locale for a New York City native who had not ventured outside the city. He worked with the Army Finance Department, which struggled to keep up with payrolls. Watching the wannabee-accountants march, Lee noticed they lacked vigor. He penned a song for them, inserting new lyrics over the famous “Air Force Song.” The peppy tune included memorable lines, like “We write, compute, sit tight, don’t shoot,” but it improved morale.

Stan used humor to help the men absorb the complex procedures. “I rewrote dull army payroll manuals to make them simpler,” Lee remembered. “I established a character called Fiscal Freddy who was trying to get paid. I made a game out of it. I had a few little gags. We were able to shorten the training period of payroll officers by more than 50 percent.” He joked: “I think I won the war single-handedly.”

“I rewrote dull army payroll manuals to make them simpler. I established a character called Fiscal Freddy who was trying to get paid. I made a game out of it. I had a few little gags. We were able to shorten the training period of payroll officers by more than 50 percent...I think I won the war single-handedly.”

Lee moved to another project, calling it “my all-time strangest assignment,” creating anti-venereal disease posters aimed at troops in Europe. Sexually transmitted diseases had plagued armies throughout history. American leaders considered the effort deadly serious. Despite implementing extensive education campaigns, the military still lost men to syphilis and gonorrhea. The British – less willing to confront the taboo epidemic – had 40,000 men a month being treated for VD during the Italian campaign.

Military leaders went to extreme measures to thwart STDs, including the creation of propaganda posters showing Hitler, Mussolini, and Tojo deliberately plotting to disable Allied troops via disease. Many of these images, such as the ones famously created by artist Arthur Szyk, depicted the Axis leaders as subhuman animals, with rat-like features or as ugly buffoons.

Unsure how to combat the scourge, Lee promoted the prophylactic stations set up by the armed forces. Men visited the huts when they thought they were infected, which involved a series of rough and painful treatments. “Those little pro stations dotted the landscape,” Stan said, “with small green lights above the entrance to make them easily recognizable.” He wrestled with different taglines, ultimately hitting upon the simplest: “VD? Not me!”

Lee illustrated the poster with a cartoon image of a happy serviceman walking into the station, the green light clearly visible. Army leaders liked its simplicity and flooded bases with the posters. Ironically, the print may have ranked among Lee’s most-seen, yet also the most roundly ignored.

According to lore, the other “playwrights” couldn’t keep up with Stan, forcing the commanding officer to order him to slow down. While it is difficult to quantify the importance of the films, posters, photos, and training aids the Signal Corps produced, analysts determined they cut training time by 30 percent. Signal Corps efforts also provided from 30 percent to 50 percent of newsreel footage for movie theaters, which kept the public informed. Lee, Capra, Geisel, and the other Army “playwrights” did vital work.

Lee used downtime to keep his fingers dipped in Timely ink and his pockets filled with Goodman’s money as a freelance writer. With the extra money, Stan purchased his first automobile for $20 – a 1936 Plymouth with a fold-up windshield. Stationed near Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, the unique windshield allowed the warm Southern air to blow in his face as he cruised the back roads of tobacco country.

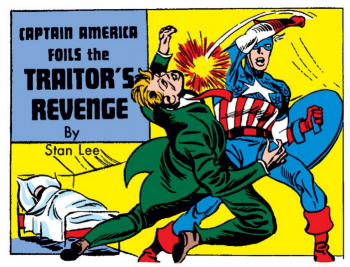

No matter where the Army sent him, Lee received letters outlining stories from Fago every Friday. Stan then typed up the scripts, sending them back on Monday. In addition to working on comics, Lee also helped out with the pulps. He wrote cartoon captions for Read! magazine, including this short ditty in January 1943: “A buzz-saw can cut you in two / A machinegun can drill you right thru / But these things are tame, compared— / To what a woman can do!” The accompanying drawing shows a plump woman feeding her bald husband – chained to a doghouse. The ribald humor fit within Goodman’s magazines, filled with sexist overtones and racy photographs.

Stan also wrote mystery-with-a-twist-ending short stories, similar to the ones in Captain America. In “Only the Blind Can See” (Joker, 1943-1944), the gag is on the reader, who eventually realizes a supposedly blind panhandler (assumed a phony) was telling the truth. Written in second person so Lee can speak directly to the reader (addressed as “Buddy”), one learns that the down-on-his-luck beggar had been too prideful. The truth comes to light when a speeding car hits the blind man. These short stories served as training for the science fiction and monster comic books that Lee would write after the war.

Stan’s afterhours writing for Timely went largely unnoticed by his superiors, but once got him arrested (in typical Lee madcap fashion). One Friday a bored mail clerk overlooked Stan’s letter, reporting an empty mailbox. Lee swung by the closed mailroom on Saturday and spied a letter in his cubby – with the Timely return address.

Fearful of missing a deadline, Lee asked the officer in charge for the letter. The harried officer told Lee to worry about the mail on Monday. Angry, Stan used a screwdriver to gently loosen the hinges and freeing the missive. When he realized what Lee did, the mailroom supervisor went berserk, reporting him to the base captain. They charged Lee with mail tampering and threatened to throw him in Leavenworth prison. Luckily, the colonel in charge of the Finance Department intervened. In this instance, Fiscal Freddy really did save the day!

***

Stan’s signature and a quick roll of his ink-stained thumb across the Army discharge papers made it official – in late September 1945 Sergeant Lee returned to civilian life. Practically before the ink dried, the 23-year old roared off base. His new black Buick convertible had hot red leather seats, flashy whitewall tires, and shiny hubcaps – a noticeable upgrade from the battered, $20 Plymouth.

Lee received a $200 bonus (called “muster out pay”), given to soldiers so they could jumpstart their post-military lives. Half went into a savings account and Lee pocketed the rest. The Army had allotted him $42.12 to get back to New York City from Camp Atterbury in central Indiana, about 50 miles south Fort Harrison.

Excited to get back to the Big Apple, Stan joked that he “burned my uniform, hopped into my car, and made it non-stop back to New York in possibly the same speed as the Concorde!” The editor desk awaited in the new headquarters on the fourteenth floor of the Empire State Building. Lee zoomed off on the 700-mile trip to the Big Apple.

Stan Lee: A Life by biographer and cultural historian Bob Batchelor